“Continuous Discovery Habits” by Teresa Torres

Drive business outcomes by discovering products your customers want

Product discovery is a set of activities done to understand customers’ needs, pains, and desires

This book presents a practical framework showing teams how to deliver business value for their companies by discovering products that deliver value for their customers

It also helps product people navigate through a paradigm-shifting mindset change, leading them to embrace uncertainty and mitigate risks through customer-centered experiments

Well after the publication of The Agile Manifesto (2001) and Lean Startup (2011), many companies still struggle to find a balance between business needs and customer needs. The work of product managers is still measured by whether the product has been shipped on-time and on-budget, rather than by the positive impact it has had on customers’ lives.

In Continuous Discovery Habits, Teresa Torres joins other present-day product leaders like Marty Cagan and Melissa Peri in calling for a change. She argues that digital products are best built by empowered product teams who choose to deliver value for their companies by first creating value for their customers.

Drawing on the principles of both Agile and Lean methodologies, she puts forth a collection of eleven habits intended to help product teams systematically discover unmet customer needs and validate their product hypotheses. Cultivate these habits continuously, Teresa writes, and you’ll increase the odds that what you build is what your customers really want.

In practical terms, the goal of discovery is to drive better product decisions through the use of customer input. But as new technologies become available and markets evolve, so do the needs, problems, and desires of customers. As a result, Teresa argues that “a digital product is never done” (p. 14). Rather than serving as a one-off event preceding delivery, product discovery is thus seen as an ongoing process enabling teams to make informed decisions and mitigate risks while adapting to the ever-changing customer and product landscape.

“Good discovery doesn’t prevent us from failing; it simply reduces the chance of failures. Failures will still happen. However, we can't be afraid of failure. Product trios need to move forward and act on what they know today, while also being prepared to be wrong.”

— Continuous Discovery Habits, p. 35

In addition to the eleven habits, this book offers a tool for visualizing the discovery process and a collection of six mindsets that will help product teams frame and reframe their decisions as they go. Taken together, they form a practical framework of product discovery activities that can be divided into four stages:

Setting a clear product outcome to help reach your company’s business goals

Discovering the opportunities which will drive that outcome by creating value for customers

Generating and validating the best solutions to address your selected opportunities

Managing your discovery work in a way that’s systematic and sustainable in the long run

1. Setting a product outcome

The goal of the first discovery stage is to establish an actionable outcome that will help your product team deliver business value. This section shows us how to get there.

By assigning product people a business goal, the company states how they can contribute to the success of the business. It is now their choice—or, as Teresa seems to be saying, their duty—to discover how to create business value by solving their customers’ problems, instead of pursuing financial goals at all cost, and likely at the expense of the customers. It’s a choice the organization can support by promoting a customer-centric mindset, one that assumes companies exist to serve their customers.

“Serving customers is how we generate profit.”

— Continuous Discovery Habits, p. 25

But when figuring out how to create business value, product managers (PMs) and their teams need to be given enough wiggle room to explore and decide how to best impact business metrics by what is within their product power to deliver. In doing so, Teresa argues, the company can support them by cultivating another mindset—becoming outcome-oriented.

Working with outcomes

Instead of telling teams what to do—which features to ship and when—the company can frame its expectations as outcomes rather than output. Given enough autonomy, a product team can work their own way toward these outcomes by leveraging their knowledge of the business, its customers, and the technology that connects them. This unique vantage point allows them to discover viable, desirable, and feasible solutions to their customers’ problems.

So, how do you move from a business outcome to a solution that works for your customers?

Clearly, capturing business value through high-level metrics (such as increased revenue, reduced churn, or a growing market share) means that business outcomes focus on the success of the company—not its customers. What’s more, such outcomes also involve shared responsibility between multiple teams, like sales and customer support, making it difficult to coordinate and assess everybody’s individual contribution.

As we shift our definition of product success away from the code that gets shipped (output) to the impact it creates in customers’ lives (outcome), we also don’t want to zero in on very low-level traction metrics. These are related to single features and, while useful for optimizing an existing product, they limit the team’s range of choice when discovering new solutions.

“We can increase the accountability of each team by assigning a metric that is relevant to their own work.”

— Continuous Discovery Habits, p. 48

According to Teresa, the best way forward is for the team to negotiate and set a product outcome that will in turn drive the business outcome. Compared with the latter, product outcomes are mid-level metrics that gauge how well the product you’re building drives company-level metrics. It also remains fully within the product team’s control, leading to increased ownership and accountability.

But there’s another benefit. Many business outcomes are lagging indicators, which measure events after they have happened. This limits the team’s capacity to respond to what they’re learning. In contrast, product outcomes can be set as leading indicators—those that help predict and plan for the changes of corresponding lagging indicators. For example, when tasked with improving customer retention (which can only be measured after the fact), you may discover how it’s affected by the customers’ initial perception of the product and then negotiate a product outcome for improving it in advance.

It’s clear that finding correlations between business and product outcomes requires some exploration in its own right. In fact, your discovery journey begins here, as you look for ways to drive business goals through product decisions. Then, once your product outcome has been set, becoming your master point of reference, you’re ready to discover the opportunities that will help you achieve that outcome by creating value for your customers.

2. Discovering opportunities

There are three checkpoints for this stage:

You’ve identified your customers’ needs and problems through interviews

You’ve found and organized a range of opportunities to address those needs

You’ve pinpointed your single top opportunity for further exploration in the next stage

People use products for many different reasons—not only to solve problems but also to perform certain tasks and improve their lives. That’s why Teresa uses the wider term of opportunities to cover the pain points, needs, and desires of customers. For the product team, these are the “opportunities to intervene in our customers’ lives in a positive way” (p. 27).

One of the main tenets of continuous discovery (CD) is that you can find such opportunities by talking to your customers at regular intervals. But how do you know which questions to ask?

Mapping what you know

Teresa recommends first mapping what you already know about your customers’ current experiences. You should use your product outcome to establish the right scope—narrow if you’re optimizing an existing solution, broad if you’re exploring neighboring markets. The resulting experience map visualizes the customer journey as it exists in that moment, showing individual events in time and their connections.

When building your map, it’s important that you look for customer experiences beyond your product alone. Let’s go back to our earlier example of increasing retention by improving the customers’ early perception of your product. Here you might want to consider how customers learn about your product and from whom, how and when they use it, and how they decide if the product creates enough value for them to continue using and paying for it.

“If you are solving a real need and your product plays an important role in your customers’ lives, they will be eager to help make it better.”

— Continuous Discovery Habits, p. 91

Once your team is aligned on what you think are the key experiences of the customer journey, you can start interviewing customers to validate these assumptions. With time, Teresa says, you should build a habit of doing so at least once a week. This will allow your team to get quick answers to the product questions you’ll be generating while you keep discovering new opportunities.

Interviewing customers

Given that human beings are notoriously hopeless at estimating and reporting on their behavior, Teresa recommends that you “excavate their stories”—ask questions that encourage customers to tell you what they actually did in the past, rather than what they think they would do. Ask helpful questions like, “Tell me about the last time you [did something]” (p. 80). You can rely on the experience map to narrow down the scope of the stories you’re looking for and look for gaps in what the customers tell you during the interviews.

“Our goal as a product trio is to collaborate in a way that leverages everyone’s expertise.”

— Continuous Discovery Habits, p. 92

A quick note about interviewing and teamwork: The third CD mindset assumes that work is most effective when performed in a collaborative manner, an idea that’s materialized through cross-functional teams that Teresa calls product trios. These are product teams composed of a PM, a designer, and an engineer—each of whom brings their unique knowledge, experience, and perspective on the product. To reduce bias, it’s critical that all activities are performed collaboratively as a team, and interviewing is no exception.

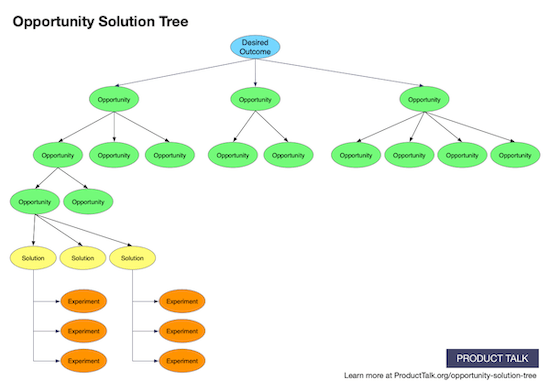

As you keep talking to your customers you’ll find patterns in their stories that will help you continuously update your experience map. You’ll also discover new opportunities to create value for your customers by addressing their problems, needs, and desires. With time, the number of these opportunities will grow to the extent that you’ll soon need to start organizing them. One way to do this is to create an opportunity solution tree (OST).

Organizing opportunities

The OST is a tool for organizing your discovery process in a visual way. Making your work visual is the fourth CD mindset advocated by Teresa, because “drawing allows us to externalize our thinking, which, in turn, helps us examine that thinking” (p. 65). She goes to great lengths explaining how to make the most of your OST; here are the basics.

The OST can be divided into three main areas. The top area of the tree is your product outcome, a point of reference that helps you identify the opportunities that can realistically contribute to achieving that outcome. Directly below it is what Teresa calls the opportunity space—that is, all the outcome-driving opportunities that are logically organized together. The bottom-most area is the solution space, which we’ll cover in the next section.

“You should be revisiting your opportunity solution tree often. You’ll continue to reframe opportunities as you learn more about what they really mean. Seemingly simple opportunities will subdivide into myriad sub-opportunities as you start exploring them in your interviews.”

— Continuous Discovery Habits, p. 112

One way to organize your opportunities is to take the main customer journey events from your experience map and put them on top of the opportunity space—these are now your parent opportunities. They can be divided into smaller child opportunities, which can themselves be divided even further. Eventually, you should end up with a tree-like structure, where opportunities branch out as they become smaller, helping you visualize two key relationships: between parents and children, and between siblings.

The main benefit of understanding the parent-child relationship is that it helps you deliver more value incrementally, rather than shipping massive chunks of work all at once. In turn, visualizing sibling relationships enables you to prioritize opportunities that are on the same level, helping your team focus on a single parent opportunity at a time.

Prioritizing opportunities

Teresa provides four criteria for sibling-level comparison that teams can use to select their top-priority opportunity—that is, one with the highest potential of driving their desired product outcome:

Opportunity sizing. Identify the frequency of a given problem or need, and how many customers could have it

Market factors. Assess how addressing an opportunity could reposition your product relative to your competitors

Company factors. Establish the impact of addressing this opportunity on your company, considering its strengths and weaknesses

Customer factors. Evaluate how important an opportunity is to your customers, and how happy they are now using existing alternatives

This work of comparing and contrasting starts at the parent-opportunity level. Once your team has agreed on the most promising parent opportunity, you move to the level below it and continue prioritizing opportunities until you reach the end of the OST branch.

Now, with your bottom-most, highest-impact opportunity selected, you’re ready to move to the next stage: this is where you’ll discover and validate the best solutions to address your chosen opportunity.

3. Generating and validating solutions

The checkpoints for this stage are the following:

You’ve generated solutions for your top opportunity and selected the best three

You’ve identified the assumptions that need to be true for each solution to work

You’ve designed and run experiments to validate the riskiest assumptions

Entering the solution space

As PMs, we spend a lot of time prioritizing—we triage issues, refine feature backlogs, and plan product roadmaps well into the future. Taking a step back, it’s easy to see how these activities are all related to building and improving already-defined solutions, often limiting teams’ capacity to strategize.

As a result, many teams implementing the Lean method’s build-measure-learn process often overinvest in building and find themselves falling into the build trap, a term popularized by Melissa Peri. Teresa seems to agree:

“The hard reality is that product strategy doesn’t happen in the solution space. Our customers don’t care about the majority of our feature releases (…) Instead, our customers care about solving their needs, pain points, and desires (…) Strategy emerges from the decisions we make about which outcomes to pursue, customers to serve, and opportunities to address.”

— Continuous Discovery Habits, p. 118

By shifting prioritization to the opportunity space, CD gives product trios room to make strategic decisions earlier in the product life cycle. This aims to restore the balance between building and knowing what to build through testing and learning, as well as bringing customers back to their rightful place in the center of product strategy.

In practical terms, setting priorities in the opportunity space better equips product trios to enter the solution space—they can start working distraction-free, already knowing that their focus is on the most impactful opportunity. Moreover, zeroing in on a single opportunity makes it easier for product teams to generate and select among several solution ideas for that opportunity.

Generating and selecting solutions

Teresa examines a range of scientific research about human psychology and creative thinking, and applies it to PM-related teamwork to suggest the following approach: work alone to generate ideas, then work as a group to select the best ones.

This is premised on the observation that individual team members perform better on divergent exercises, which involve creative thinking, because they’re not biased by groupthink and constrained by the rules of group conformity. In contrast, groups tend to perform better on convergent exercises because they have the richer, collective group experience at their disposal.

After having generated enough ideas, teams should vote for the three solutions they think will make for the most promising initial set—one composed of three solutions that are diverse and have the highest potential of fulfilling the top opportunity selected earlier.

“[Earlier] you made a strategic decision when you chose a target opportunity. Don’t undo that work now.”

— Continuous Discovery Habits, p. 142

So why select only one opportunity and as many as three solution ideas?

While working in the opportunity space, you want your team focused on delivering value as early as possible, so you converge. This helps you to strategize in preparation for entering the solution space. In contrast, while working with solutions, you want to diverge and look for different options to avoid two common problems—confirmation bias and escalation of commitment. As solutions are less abstract than opportunities, it’s easier to get attached to and over-invest in a single idea. Also, switching between three ideas decreases the time you spend thinking about and working with each individual idea, thus also reducing your (still not validated) commitment.

What you have at this point are the three most impactful solutions; what you don’t have is the time to validate them all. To speed up learning and streamline decision-making, Teresa advises product trios to run small tests in quick iterations. However, given that testing solutions is anything but small and quick, we need to resort to only testing their key underlying assumptions.

Identifying assumptions behind solution ideas

Approaching your work in an experimental way is the fifth CD mindset, one that encourages you to think and act like a scientist—come up with the hypotheses you’d like to test, pre-define a set of clear test-success criteria, and then run experiments to prove your hypotheses true or false. In the case of testing solution ideas, your hypotheses are the assumptions that need to be true for your solutions to work and, eventually, fulfill the top opportunity.

“The biggest barrier to testing assumptions is becoming aware of the assumptions we are making.”

— Continuous Discovery Habits, p. 146

There are five types of assumptions related to the following product aspects:

Desirability. Will customers find the product valuable and want to use it?

Viability. Will our company derive business value from building and maintaining it?

Feasibility. Will we be able to build it in such a way that it creates value for customers?

Usability. Will customers be able to use the product to derive expected value?

Ethical. Will we introduce any potential harm to customers and society at large?

Teresa admits her teams often generate in excess of twenty assumptions of all five types for each of the three ideas. Because trios rarely have the capacity to quickly validate so many assumptions per opportunity, they should only test those carrying the greatest risk of derailing their solutions if proven wrong. Known in the Lean world as the leap-of-faith assumptions, they are supported by the weakest evidence and are the hardest to work around if found incorrect later.

In this light, the goal of product experiments is to gather stronger evidence on the key assumptions underlying selected solution ideas.

Designing and running experiments

That’s a point worth noting—ideas generated for a single opportunity often share a number of assumptions or, in other words, a given assumption may underlie more than a single idea. This, according to Teresa, is precisely what makes testing assumptions so effective as opposed to testing the solutions themselves: not only are your experiments quicker to run because you’re gathering data on a set of ideas at a time, but they also yield results that are applicable to the larger set, helping you to compare your ideas later.

With this in mind, there are four rules of thumb for designing and running product experiments.

First, design and run your experiments as simulations of the actual user experience. This will allow your team to observe and analyze participants’ actual (if somewhat simulated) behavior, rather than having to rely on what they say they would do under given circumstances.

Second, define clear success criteria for your tests before you run them. A shared understanding of what it takes for the test to pass reduces the risk of confirmation bias kicking in during results interpretation, as well as making your findings more actionable. As a team, decide how many participants out of the total test sample should exhibit a given behavior. It’s only by setting that number in advance, and then observing it under test conditions, that you’ll be able to confidently move your key assumptions higher on the scale of evidence strength.

“We want to design our tests to learn as much as we can from failures.”

— Continuous Discovery Habits, p. 181

Which brings us to the third rule. Defining the “how many out of how many” number in advance is also helpful for determining the optimal size of a test. Paraphrasing a famous quote, the rule of thumb here is that tests should be made as small as possible (so that you’re able to run them quickly), but no smaller (so that you get actionable results for your team).

Each subsequent experiment reduces the risk for a set of assumptions, prompting continuous re-evaluation of that risk. As a team, you should decide whether to continue testing a given assumption, using bigger and costlier experiments, or switch to the now-riskiest assumption. The final rule of thumb says that you should experiment until you feel that (1) enough risk has been removed, or that (2) running another assumption test would be costlier than building the actual solution.

4. Managing discovery work

Let’s bring everything together.

This section covers product discovery management by looking at what we’ve learned so far, but in reverse order, moving our attention away from the steps—a useful simplification when learning about CD—to the areas of the discovery process. Thinking in areas is important because, as Teresa argues, ongoing discovery work is never linear; instead, it runs in cycles.

It’s helpful to understand the management of discovery cycles as performing sets of activities that can either run within a single discovery area or span multiple areas if necessary. For simplicity, let’s assume there are three discovery areas that correspond with the three spaces of the OST:

The solution area. Where we test assumptions and prototype solutions

The opportunity area. Where we compare opportunities and strategize

The outcome area. Where we gauge the impact of our work on the business outcome

Managing the solution area

The goal of the cycles running within this area is to choose the best solution idea by de-risking key assumptions through product experiments. Each subsequent cycle brings more information for your team, thus reducing the risk associated with implementing what you think is the best solution.

Both the experiments and the implementation run on data. You need data to decide if your assumption tests corroborate your earlier hypotheses and which assumptions need further testing. Data comes from instrumenting your product and measuring its performance, allowing your team to draw better experiment conclusions and evaluate the solution’s impact on your target opportunity further down the road.

In addition, increasingly elaborate experiments quickly start to require real data about customers’ real behavior, as opposed to test data derived from simulated experience. What this means for your team is early deployment of live prototypes in the production environment. This is where discovery meets delivery, triggering the self-reinforcing cycle of building, measuring, and learning. Implementing your solution and measuring its impact will generate new questions, and pave the way for more discovery.

As a result, newly available information may at some point disprove your team’s earlier hypotheses, which is when working with cycles will help you take a step back and rethink the course of action. It’s worth reiterating that CD is about making sound data-driven decisions, no matter if this means repeating experiments with new data, re-evaluating assumption risks, or even reverting to another discovery area.

“Course-corrections should be celebrated. The fruit of discovery work is often the time we save when we decide not to build something.”

— Continuous Discovery Habits, p. 199

Subsequent cycles within this area may render your target opportunity no longer worth pursuing or get you implementing what you believed was the best solution. Either way you go, you’ll find yourself wanting to switch opportunities, leading you to the higher-level area of discovery work.

Managing the opportunity area

Returning to this area is a chance to revisit your team’s earlier ideas and priorities. You are now equipped with new information on the customer experience, allowing you to update the experience map and reprioritize the opportunity space. Some of the previously defined opportunities may no longer be true, possibly leading to your going higher up the OST ladder and honing in on another parent opportunity.

Re-entering the opportunity space, it’s worth keeping in mind that certain opportunities may currently be out of your team’s reach owing to their complexity or other factors. When faced with a bigger opportunity that cannot be addressed right away, Teresa recommends teams do the necessary preparations first. Interestingly, she encourages teams to start preparing the impactful opportunities to be addressed further down the line while at the same time working on the more available opportunities. “If we can deliver impact this week, we should” (p. 207), she writes, offering a possible justification for deviating from the “one opportunity at a time” rule we covered earlier.

The cycles performed within the opportunity area can either lead you back to the solution area or result in a growing number of opportunities being delivered by your team—which will make you want to zoom out again and measure how your work affects the product outcome.

Managing the outcome area

As you address subsequent child opportunities, you are getting closer to fulfilling their parent opportunities. This, in turn, should help drive the product outcome. Your team can now reap the rewards of instrumenting the product earlier while managing the solution area, providing sufficient information to assess the impact of your work.

Managing the outcome area, you’ll eventually need to engage in yet another kind of long-term discovery cycle. This is where your team will track, measure, and reinforce the impact of your product work on the business outcome, which is where you’ve been headed all along.

“It feels good when customers engage with what we build. But sadly, satisfying a customer need is not our only job. We need to remember that our goal is to satisfy customer needs while creating value for our business.”

— Continuous Discovery Habits, p. 194

Managing discovery cycles within multiple areas may inadvertently lead product teams to lose sight of the broader business perspective. Similarly, getting close to the needs, pain points, and desires of the customers might result in their excessively focusing on product desirability at the expense of business viability. However, Teresa’s message is that, if done in a systematic way, CD helps PMs keep track of all the three discovery areas, allowing them to sustainably deliver business value by first creating value for their customers.

To reach that balance and maintain it in the long run, Teresa advises product trios to cultivate the sixth and final CD mindset, which rather unsurprisingly assumes that discovery work should be performed… well, continuously. This entails building a framework for making new customer input available every week, as well as using that input to guide the trio’s decisions throughout the entire product life cycle.

Because no product will serve customers without a thriving business to support it, it is by adopting that continuous perspective that product teams can drive business outcomes by discovering, building, and growing products their customers want.

What else you’ll learn from this book

How to negotiate an actionable product outcome with your product leader

How to improve your team’s performance by setting learning goals

How to use interview snapshots to record, analyze, and share your customer interview learnings

How to deploy a range of techniques to discover assumptions of different types

How to use the OST to manage communication with key stakeholders and invite them to co-create with your team

How to advocate for and start practicing continuous discovery habits if your organization is yet to embrace the benefits of product discovery

My thoughts

Discovering brand-new products. In my own work, while seeking opportunities to create new value for new customers, my team and I struggled to adjust the CD framework (as laid down in the book) to our needs. Teresa argues that her framework enables teams “to discover brand-new products and to iterate on existing ones” (p. 14). However, you cannot help but feel that the book’s focus is almost exclusively on improving already-existing products.

Two things helped my team get up and running:

Defining early on a set of hypotheses about our value proposition, our target customer segment, and the problem we’re trying to solve for them, followed by a round of quick experiments aiming to disprove these hypotheses (you can sense clear Lean Canvas influences here).

Investigating how the problem is solved today, which was helpful for (1) creating the experience map that we later used to define parent-level opportunities, and (2) exploring relevant unit economics with a view to assessing the viability of our business model further down the road.

Teresa referred to these issues in a blog article dedicated to discovery in early-stage startups. She stressed the importance of kicking off the CD process by defining your value proposition and customer segment, as well as introducing the concept of directional outcomes. For details, see the Dig deeper section below.

You are going to be wrong. One of the biggest advantages of having my teammates and key stakeholders read Teresa’s book was to get everyone aligned on what product discovery is essentially about—risk mitigation.

Again, there were two key things we did that helped bring everybody on board:

Working with outcomes rather than outputs, which allowed us to expect, communicate, and eventually embrace uncertainty—as opposed to having to rely on “a fixed roadmap [that] communicates false certainty” (p. 45).

Making use of what Teresa calls two-way door decisions; by understanding that a vast majority of our product decisions can be reversed, our team was able to overcome analysis paralysis and act more confidently, knowing that “we’ll learn more from testing our decisions than we will from trying to make perfect decisions” (p. 125)

The seventh mindset. The latter was additionally reinforced by what was likely my most important takeaway—the compare-and-contrast work that you perform on opportunities, solutions, and assumptions. Rather than making yes-or-no decisions, Teresa encourages product teams to compare and contrast their options with a view toward always leaving an open door to return to, as well as giving them confidence to act even without all the data in place. With so many benefits applicable to all three discovery areas, you might be surprised Teresa didn’t consider “comparative” as the seventh full-fledged CD mindset!

Dig deeper

Visit Teresa’s website at producttalk.org.

Be sure not to miss her blog, where she explores some of the topics covered in the book in greater detail, including:

The first principles of product discovery (parts one, two, and three)

Sharing responsibilities among the members of the product trio (link)

Getting the most out of continuous discovery if you’re an early-stage startup (link)

Teresa Torres. Continuous Discovery Habits: Discover Products That Create Customer Value and Business Value. Product Talk, 2021. 244 pages. Buy on Amazon